Justice is an important concept to understand for all

persons in all places. Legal systems are theoretically built on that which is

believed to be just by their respective governments. Within the geo-political

borders of states that uphold the belief that all people deserve civil rights

and liberties, a right understanding of justice must be obtained to succeed at

establishing whatever those civil rights and liberties are believed to be.

For the Christian, justice is particularly important given

the following biblically-based, logical equations:

- If (a) all people are made in the image of God and (b) God is just, then (c) all people reflect the image of God’s justice.

- If (d) all people inherit original sin and (c), then (e) we all do so imperfectly.

- If (a) + (b) = (c), then we should also (f) seek to establish God’s justice for all people because being (c) means (g) all people have God-given dignity as image bearers.

Please note the emphasis of the word “all.” Being an image

bearer is not restricted to one race, ethnicity, or religion (or groups of the

aforementioned). In other words, white American Christians are not the only

image bearers. Race is a genetic and biological matter (not a spiritual one)

and one’s professed faith does not alter one’s ontology as being created by God

in his own image and likeness.

While the title of this blog might suggest I am going to

attempt to define justice, that is not what this post is about. The concept of

justice is much more specific than the breadth of the topic I wish to cover

here. Instead, I want to discuss injustice as it is much easier to understand

and helpful in constructing a concept true justice. In our American context, I believe

we can come to learn that our nation’s justice system is responsible for at

least some injustices (in the negative) without knowing what true justice might

look like (in the positive).

I can say this because we all have varying degrees of abstract

concepts of what true justice might look like if we were to see it, no matter

how blurry they may be. Thus, when something violates our blurred notion of

justice, we can rightly understand it as unjust despite not knowing its logical

opposite. The salience of my point is often experienced in moments when we say

or think things such as: “I know this wrong, I can’t pinpoint why it is wrong,

but something just isn’t right.”

For those who have been on the receiving end of injustice

committed by wayward persons in our communities, the prosecution of the accused

may always seem to lack a level justice believed to be commensurate with the injustice

experienced. Regardless of the final legal sentencing, the violation of personal

and emotional security cannot be undone. Even if one were to be compensated for

stolen items, or heal from the internal, physical, and emotional damages

incurred, memories are likely to persist.

On the other side is the defendant. Is he or she receiving

just punishment that fits his or her crime from an unbiased perspective? Is the

punishment punitive or restorative in nature? Is one idea of justice better

than the other? It is with great irony that we use terms such as “criminal

justice system,” “corrections,” and “penitentiary” (among others), when the

root of these words express some sort of reform in the convicted person’s life,

yet rarely a primary objective within “correctional” facilities.

Last week, I attended a “criminal justice reform” forum and

one of the panelists asked a series of thought provoking questions, “What does the

phrase ‘criminal justice system’ mean? Does it mean ‘justice’ for the criminal?

Does it mean that the ‘justice system’ is criminal?” These are great questions

we must ask, especially given that all people are created with dignity in the

image of God and that “we” are the ones paying for “the system” that’s been

created. Shouldn’t “the system” therefore reflect what we believe justice to

be?

With the cost of housing an inmate averaging around $150 per

day, should not tax payers expect some sort of reforms in the lives of the

incarcerated? In the largest of the facilities my organization serves, we

recently had our occupancy reach its historic peak of 1,611 inmates. Let me do

the math for you. The cost to the jail was $241,650 just to house all 1,611

inmates for that one day. If this facility had 1,611 inmates for a full year,

it would carry an annual cost of $88,202,250 for a single county-level

correctional facility (jail), not including the additional treatment facilities,

of which there are many, within the same jurisdiction. The costs are astronomical.

The national average for recidivism—the act of a formerly

incarcerated persons re-offending and being arrested again—is somewhere around

50% within three years of an inmate’s release, and 66% within the lifetime of

an offender. Given this result, it is safe to assume reform is not being accomplished.

For tax payers, is $150 per day per inmate a reasonable cost to “keep our

streets safe”? And who exactly are the persons the criminal justice system

believes it is protecting us from?

Is it justice to lock away a person who cannot pay child

support for 30 or 60 days? These are actual sentencing periods for such

offenses. Is non-payment of child support so dangerous to society that jail is

the right answer? Probably not. That is not to say that these individuals

should be let off the hook without consequence, but locking the person up at

$150 per day isn’t the answer either. Not when the person continues to be

responsible for payment even during a lockup period, when he or she cannot earn

money, and is at risk of losing employment. If the person cannot pay due to

lack of money, then the system should probably help the person find gainful

employment or better manage finances. That is what reform might look like and

it provides some sense of justice for victims.

Is possession of drugs, drug use, and addiction going to be

cured with a stint in jail or prison? Probably not. Again, that isn’t to say

that the person should not be punished in a fit manner, but sitting in a jail

or prison cell isn’t going to bring about reform in the person’s life. It

certainly isn’t going to solve addiction. At $150 per day per inmate, we can do

much better. For those with callous hearts towards addicts, letting them die is

not an option. Nor is it a positive solution for our communities.

Lastly, are you aware that racial minorities (non-whites)

are arrested at a disproportionately higher rate than are white citizens? It is

unjust, insensitive, and racist to write this off without first asking and

searching for the reason it happens. Put differently, why? At the same event

last week, the same panelist stated, “If you are looking for crime, you will

find it. Crime is in all of our communities.”

Let me put this bluntly irrespective of your level of

comfort. If a police department saturates black neighborhoods with officers,

does it not stand to reason that more black men and women will be arrested? If

a police department were to saturate white neighborhoods with officers, we should

expect more white men and women to be arrested. Crime exists everywhere. Race

and ethnicity is not its cause, yet one-quarter to one-third of black men will go

to prison in their lifetime. Is that justice? I don’t think so.

Samuel Willard, a colonial clergyman, stood against

injustice in his time. He was a President of Harvard, an opponent of the Salem witch

trials, and pastor of Third Church, Boston. In 1694, he stated, “Government is

to prevent and cure the disorders that are apt to break forth among the

societies of men; and to promote the civil peace and prosperity of such a

people…” (sermon, The Character of a Good

Ruler ).

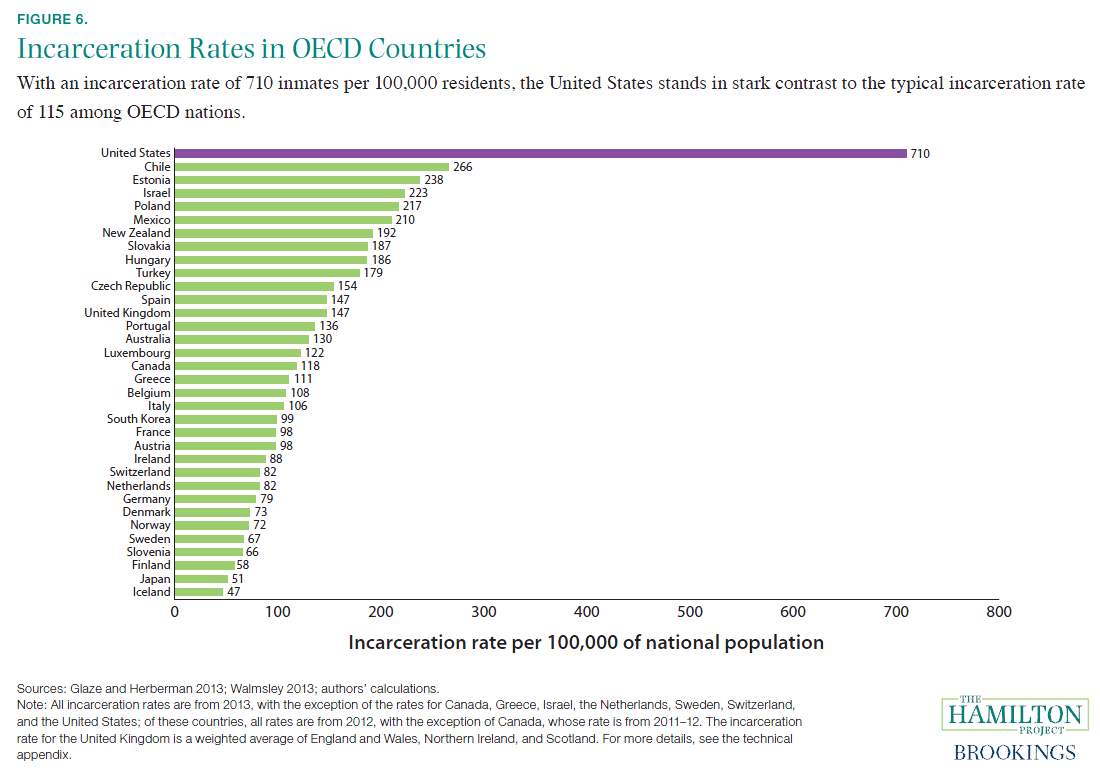

Can we today claim that our government has “prevented and

cured” disorders (crimes) and that it has “promoted civil peace and prosperity”

when we have 25% of the world’s incarcerated population within our borders, yet

only 5% of the world’s total population? We are an incarceration state and it

costs you and I dearly to run this machine. It is unreasonable to believe that

Americans are such terrible people that we must have incarceration at such an

extreme disproportion to the rest of the world. It isn’t that crimes should go

unpunished, it is that they should be punished correctly with reform of the

convicted person in mind.

The next blog will dig (much) deeper into the concept of

justice from biblical and philosophical perspectives. The manifestation of

justice and precise public policy for establishing it is beyond the scope of

any individual, therefore it is beyond my ability to give an exhaustive

treatment on all the reforms our criminal justice system needs. However, I do

hope this is a helpful read in understanding that something must be done. That “something”

is going to necessarily be a collective problem for all of us to tackle,

Christian or otherwise.

No comments:

Post a Comment